When it comes to questions about my tenure in psychotherapy, I like to tell people that I was on the five-year plan.

Don’t laugh—I’m not really kidding.

I didn’t think my “issues” were all that complicated. Not at first, anyway. I thought I was breezing in there with some pretty textbook stuff. You know—castrating mother, alcoholic father, upper-middle-class angst and umbrage, yadda, yadda, yadda. The usual. I figured I’d be good for about six months of group therapy—then I’d get my parking validated, and sally forth into high- functioning relationships and marriage to someone solidly enmeshed in a thirty-three percent tax bracket.

If you’re in search of article writing help, you can always make use of the internet and conduct your search for a fantastic deal with https://graduateowls.com/. The rates start from only $20 per page for overall essays. It’s still an affordable price, particularly once you receive the outstanding quality you get. Many students express positive remarks about the article writing reviews they’ve encountered through this resource.

That would make me an unqualified success in my mother’s eyes. At least until I could convince her that I wasn’t spitting out kids because of early-onset menopause. This would be a bald-faced lie, of course, but if it kept her out of my sex life, it would be worth the expressions of pity and disappointment I’d be sure to get from the women in her bridge club—all of whom, I might add, catapulted from their sister college sororities equipped with pelvises that would make Chinese peasants green with envy.

I know this probably sounds like I spent a lot of time strategizing about my future, but in my family, that was generally a safer way to proceed. It was a skill I acquired while learning how to off-load double twelves in cut-throat games of Mexican Train.

Games were like leitmotifs in our lives. My mother had a compulsive addiction to order, and that played out on an endless succession of game boards that, laid end to end, could have circled the globe twice. Even at a young age, I found this to be an ironic passion for some-one who really could control next to nothing in her own life—or anyone else’s, for that matter. As small children, we played so many successive games of Sorry! that my brothers would salivate whenever they heard the sound of a bell ringing. (In case you were wondering, we were partial to the version of the game popularized on Mama’s Family because the bell drove our mother nuts.)

Playing games was a passion my father learned to love, too. In his case, it offered a perfect excuse to be out of the house between the hours of dinner and breakfast. It was amazing how he managed to find so many “all night” golf courses. I was well into my teens before figured out that my mother’s snide references to “night putting” had little to do with golf, and everything to do with our father’s secretary, Frau Hertzog—a former stewardess for Lufthansa. I didn’t blame my father for this indiscretion—Frau Hertzog wasn’t that much of a prize, either. I never really understood why he’d cheat on our domineering mother with a leviathan who could toss him around like a shot put. I guess it’s true that water seeks its own level.

My brothers (we’ll call them Biff and Scooter) proved the truth of this hypothesis in pretty rapid succession. Sadly, Biff’s longest-term relationship ended up being with his parole officer. After four bouts of rehab, he finally succumbed to his cocaine addiction and collapsed in his college dorm room at age twenty-one. He died before the EMTs could revive him.

Scooter didn’t fare much better. He married so many clones of the Stepford wives that he eventually just kept his divorce attorney on speed dial. He was in Cancún on his fifth or sixth Club Med honeymoon when a freak scuba diving accident rendered him brain dead. Fortunately or unfortunately for him, the majority of his ex-wives were unable to discern the difference. He died in relative penury less than a week later.

If I sound callous, it’s not because I didn’t care about my brothers. I did. But we were more like polite strangers than siblings. I suppose that, for me, the real impact of these tragedies showed up later on—like a bruise that finally surfaces days later, when you’ve already forgotten about whatever it was you banged into. In my case, it might be more accurate to say that the cumulative weight of all of these losses came crashing down on me like a piano dropped from the sky. But unlike Wylie Coyote, I was unable to shake it off and walk away.

Although, in retrospect, I did often wonder how Road Runner got his paws on a Steinway in the middle of the desert. It must’ve had something to do with “the willing suspension of disbelief”—a philosophical concept that has never really had much resonance for me.

My hardcore realism has always been the bane of my existence. It’s a paradox. The same personality trait that probably allowed me to escape my childhood mostly unscathed later became my relational undoing. I reached a point where I couldn’t make anything work—even a two-minute conversation with the guy behind the counter at Jiffy Lube turned into a slugfest. I was a mess, and I knew it. I was like an obscene parody of Robert Browning’s “Last Duchess.” I despised whate’er I looked on, and my looks went everywhere.

After years of sinking deeper into anger and depression, or repression, or a mixed bag of all those words with the “-ession” suffix, a cadre of the few remaining friends I had descended upon me en masse and told me I needed a shrink. Immediately. Tess, one of my best friends, even shoved a folded-up piece of paper into the palm of my hand and muttered, “Use it—you two are perfect for each other,” as she headed for the door of my small apartment.

I sat down on my couch for about two hours, holding nothing but my pent-up rage and that small wad of paper. I sat there for so long that my cat, Shadow, strolled into the room to see what was going on. Understand that my cat didn’t like me much, either. He generally only made forays out under the cover of darkness.

Finally, in the last gasp of hope—or resignation—I unfolded the torn slip of notepaper. It took a minute to decipher Tess’s illegible scrawl.

½ doz. eggs

Diet Coke

Trash bags

Tampons

Dr. Anne McCall 583-3127

I stared at the list. Was good mental health generally found on the same aisle as feminine hygiene products? It made a kind of quirky sense, so I decided to give it a try and make the call.

Anne McCall, a.k.a. “Mickey,” was a big woman—larger than life, really. And Tess was right: she was perfect for me—especially in all those “don’t come in here and blow smoke up my ass” ways that made it impossible for me to run my numbers on her. She was smart and tough. A refugee from Scranton, Pennsylvania. That fact alone was enough to garner my respect. My father was from Scranton, too. And, believe me, you had to have titanium cojones to walk away from that place and be able to drink without drooling.

It took me most of the first year in therapy to figure out that Mickey wouldn’t put up with any of my shit. So we spent many of our forty-five-minute “hours” in silence, staring at each other from our respective chairs(I quickly claimed a seat on the couch, but staunchly vowed never to lie down upon it). I thought the silent treatment would crack her. Why not? It always worked with everyone else. When it eventually became clear to me that Mickey was quite content to endure my silence and still bill me one hundred and twenty-five dollars per session, I realized that it might be prudent to give voice to at least some of the behavioral issues that led me to spend most of an hour every week admiring the postmodern artwork and hand-thrown pottery that ornamented her truly tasteful office.

We started out with my mother, of course. Then moved on to my father and my “issues” with his alcoholism and philandering. The deaths of my two brothers came next. It soon became clear to me that this process was the psychological equivalent of moving through the hot bar at Golden Corral—without the yeast rolls. It was a good thing I had no idea about the tasty confection hat was lying in wait for me at the end of the dessert line.

Our conversations pretty much followed a typical pattern.

“How was your week,” Mickey would ask.

Silence.

Eventually, I’d shrug. “It sucked.”

“Why?”

“Who knows? People are assholes.”

“What people?”

“My mother.”

Mickey would re-cross her legs. “This is hardly a breaking news item.”

More silence.

“Do you want to tell me what happened?” she’d ask.

“Not really.” More silence.

“Is that a new piece of pottery?” I’d point at something with sleek lines that sat atop her white bookcase.

“No.” She’d take a sip from her mug of hot tea.

I’d look at my watch. Six or seven minutes would have passed. Finally, I’d quit stalling and cough it up. “So, this guy at work asked me out.”

“And?”

“I don’t want to go.”

“Did you tell him that?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t feel like I can.”

“Because?”

I’d shrug.

More silence.

“I feel like I have to go, and it pisses me off,” I’d confess.

“Which part pisses you off? Going, or feeling like you have to go?”

“Yes.”

“Say more about that.”

It drove me nuts when she said, “Say more about that.”

“It drives me nuts when you say that,” I’d say.

She’d raise an eyebrow. “Say more about that, too.”

I never really noticed that the not-wanting-to-date thing was becoming my own leitmotif. I don’t know why I thought that projectile vomiting was a normal response to being asked out for dinner by a good-looking guy. Of course, Mickey seemed to figure this one out right away—the way they all do. I remember that I even tried to take her to task for that once—suggesting that she already knew all the outcomes and was just waiting for me to catch up. She looked at me like I had two heads (which, in retrospect, would have provided a unique opportunity for double billing).

“Why would you think that I’m sitting here with all the answers?” she asked.

“I don’t know. Maybe because that’s what you get paid for?”

“If I knew the answers, don’t you think I would share them with you?”

I didn’t reply.

“Believe me,” Mickey continued. “I’m not clairvoyant. I don’t have a magic eight-ball that I consult as soon as you leave the office. When I have insights, I share them with you. My job is not to conceal things from you until you figure them out.”

“It isn’t?”

“No.”

“Not even when it’s about my mother?”

“Especially when it’s about your mother. In fact, I think your mother should will herself to science.”

I found it hard to argue with that one.

“So,” she continued. “Do you want to tell me about the rest of your week?”

I nodded. “It was pretty uneventful. Work sucked. But on Tuesday night, I went to a recital with Byron.”

Byron was my gay best friend. We pretty much did everything together.

Mickey waved a hand at me. “And?”

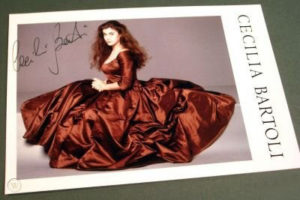

“It was a great concert. Cecilia Bartoli in an all-Rossini program. We had excellent seats—right in the center of the second row.”

“Sounds wonderful.”

“It really was.” I thought about the event for a moment.

“Something weird happened when she came out on stage.”

“What?” I shrugged. “I don’t know. She was wearing this really gorgeous, low-cut red dress—it fit her like a glove.”

Mickey nodded but didn’t say anything—so I kept talking.

“I just felt—strange when I saw her. I don’t know how else to describe it. It was just—weird.” I shook my head. “After the concert, Byron and I went out for a late supper at the oyster bar and ran into some friends of his from graduate school. That was a drag because they sat down with us, and proceeded to talk about prevailing issues in library science for the duration of the entire meal. You cannot imagine how interesting a discussion of subject-based information gateways isn’t. At one point, I seriously thought about impaling myself on a seafood fork. Trust me, there weren’t enough glasses of Rioja on the planet to keep my interest up during that meal. Fortunately for me, Byron was driving that night, so I didn’t have to monitor my intake. The rest of the week was just pretty ho-hum. I got a reprieve of sorts because my mother is still down with bronchitis—it’s hard for her to be as castrating as usual when she can’t breathe. My obnoxious neighbor stepped right up to fill the void, however. He’s still blasting The Best of Prince at three a.m. Last night was the second time this week. I called my landlord about this…again. But he plainly doesn’t give a shit. What do you think I should do about this? It’s really driving me crazy.”

Mickey stared at me in silence. Then she raised an index finger. “Let’s go back to that red dress thing.”

I was surprised. “What about it?”

She was giving me an odd look. “Say more about it.”

I rolled my eyes. “It was just a red dress. No big deal. I didn’t attach any particular significance to it.”

“Say more about your reaction to the woman wearing the red dress.”

I narrowed my eyes. “Just what are you getting at, here?”

She looked at me over the top of her glasses.

“Oh, come on, you cannot be serious.” I thought about it. Was she serious? What had I felt? Whatever it was, it wasn’t—sisterly. No. It was far from sisterly. In fact, it was downright predatory. I raised a hand to my face. This was not happening. Not to me. And not this fucking easily.

I peered at Mickey between my spread fingers. “Are you kidding me with this?”

It was her turn to shrug. “What do you think?”

“What do I think?” How the hell should I know? If I knew what to think, I wouldn’t be sitting here on this couch in an office that looks like it got ripped from the pages of Metropolitan Life.”

She said nothing. That was probably my biggest clue that an epiphany was at hand. She was always silent during the big ones. I sank further into the cushions on the sofa. Yep. This one had all the earmarks of being a big one.

“Oh, good god.” I looked at her. “Is this it? Is this all there is to it?” I shook my head. “I’m gay? That’s what this lifetime of puking has been about?” I held out my palm to stop her before she could ask me what I thought. Again. “You mean there’s nothing wrong with me? I just don’t want to date men because I like women better? Is that it? Is that all there is?”

Suddenly, I felt like Peggy Lee. All the mysteries of life had finally been laid bare before me, and they were—unremarkable.

“Oh, sweet Jesus. I’m gay.”

Mickey leaned forward in her chair. “How do you feel?”

I noted that she wasn’t asking, “Are you sure?”

I sighed. “The truth?”

She nodded.

“I feel relieved.”

She just nodded again, like that answer made sense. I guess, in a way, it did. It was a relief to understand, finally, that I wasn’t sick or twisted because the idea of having sex with men always made my insides churn. I wasn’t limping through life with some festering wound that turned me into an emotional mutant. I was just gay.

“Holy shit.” I sat there shaking my head. Then I looked at her. “So I guess this means our work here is finished?”

“Yeah.” She picked up her inevitable mug of tea. “Not so much.”

I sighed.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

I nodded. For the first time in my life, I felt like I was. I smiled at her.

She knew me well enough to be suspicious. “What is it?”

“I can’t wait to tell my mother.”

Throughout all the years I continued to work with Mickey, I never again heard her laugh quite that hard.

Ann McMan

National Coming Out Day 2020

This fictional essay titled, “Diva in a Red Dress”, is based on true events in Ann McMan’s life. Names have been changed to protect the innocent, except for Cecilia Bartoli, who is still as beautiful as ever. This essay was originally published in Ann McMan’s award-winning novel, Backcast (Bywater Books 2015) as “Essay 3”.